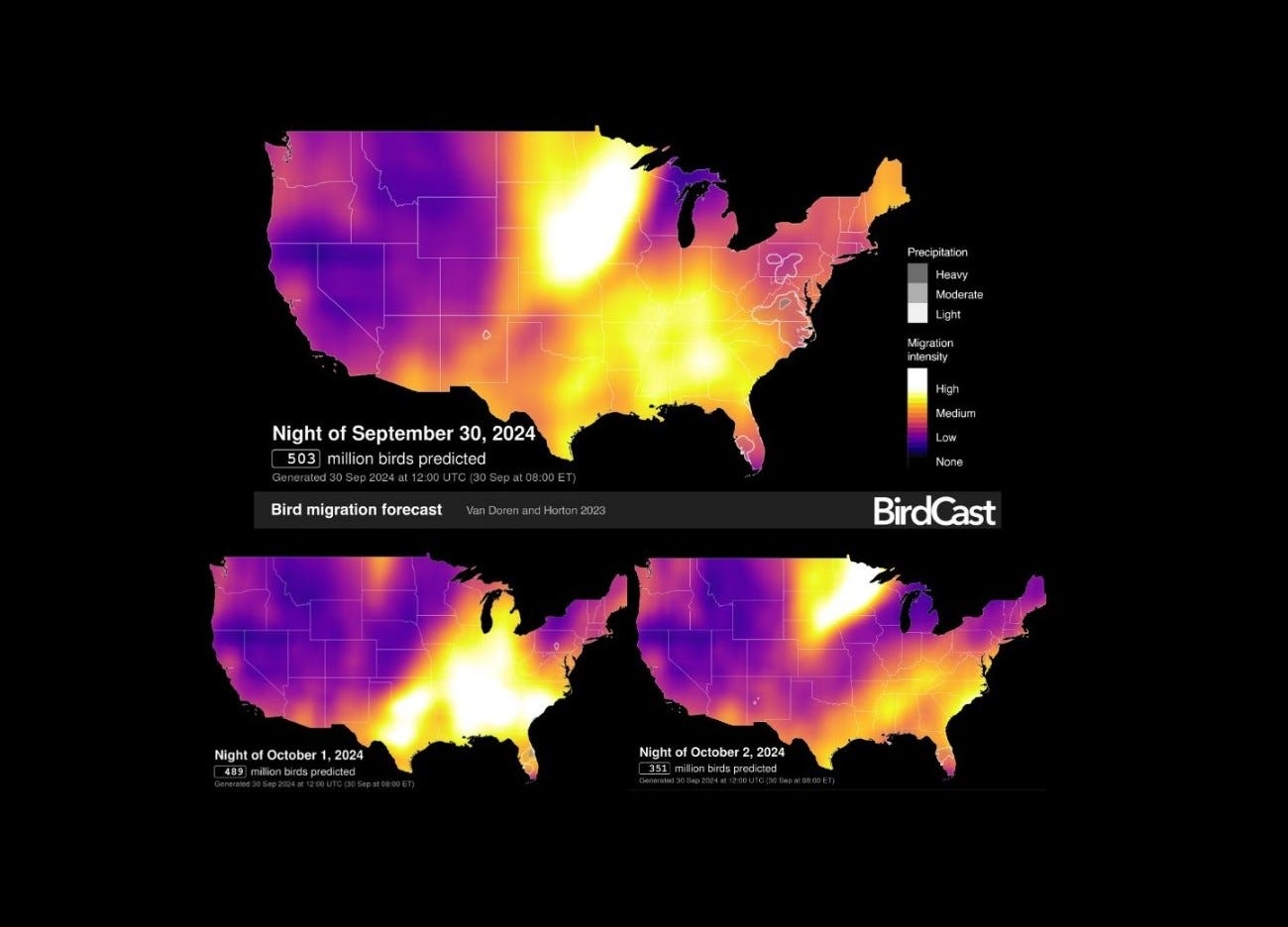

The Ruddy Turnstone is among the more than one billion birds estimated to be migrating from North America this week.

Bird of the World from the Cornell Lab provides the following information:

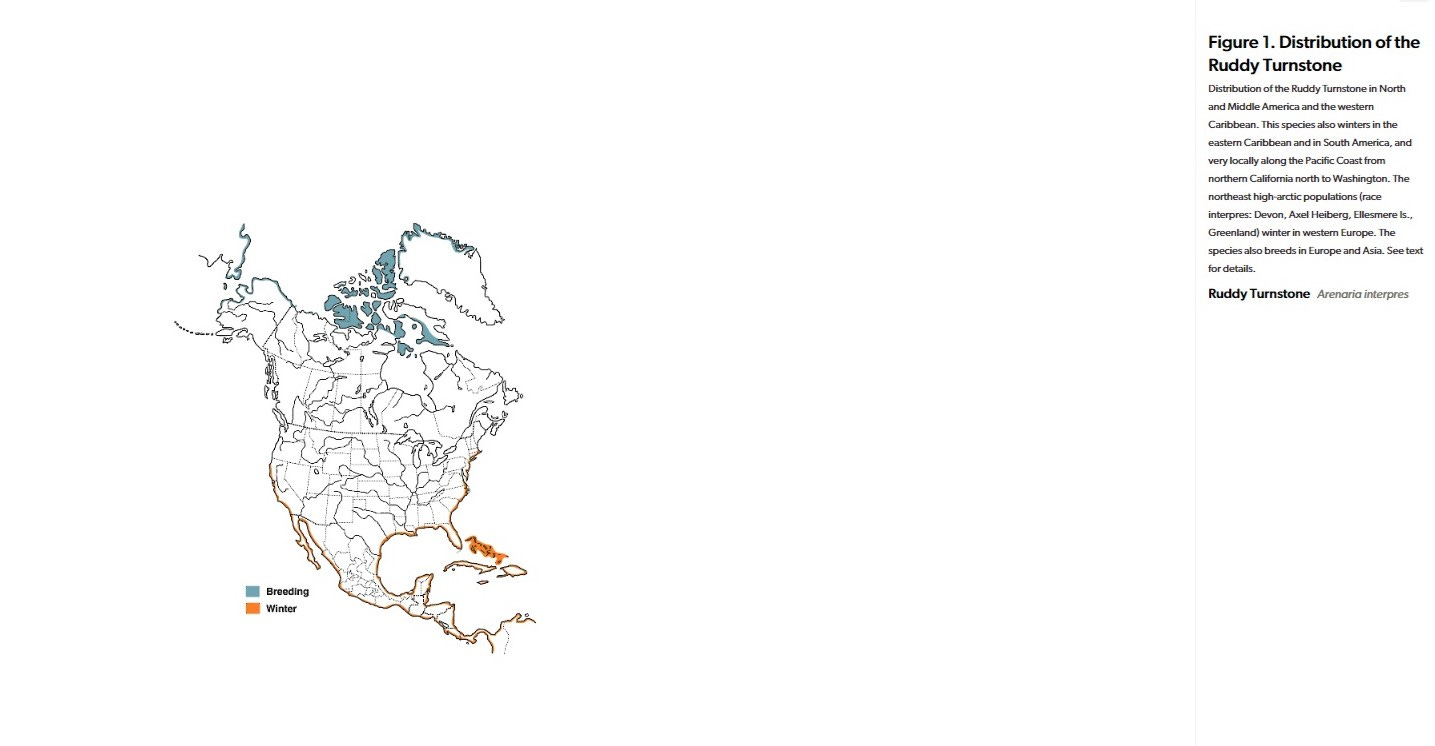

“The Ruddy Turnstone, a small, robust, Holarctic shorebird, is 1 of 2 species that make up the genus Arenaria and 1 of the most northerly breeding species of shorebirds. Although well known from its migratory movements and winter distributions on southern seacoasts throughout the world, its summer activities on the breeding grounds have only recently received attention and remain poorly known, particularly in northern parts of its range. In North America, its breeding biology remains largely unstudied. It breeds in tundra regions of northern North America from Alaska to Greenland (Figure 1). High-arctic Canadian and Greenland birds winter mainly along coastal shores in Britain and Ireland and south along the Atlantic coast of southwestern Europe (Iberian Peninsula) and northwestern Africa (some farther south); those breeding south and west of north Devon Island, Nunavut, winter mostly in northern Brazil, but also along both coasts of North and Central America from Long Island (New York) and coastal Gulf of Mexico and central California south through the West Indies and along coastal South America to Tierra del Fuego (Figure 1).”

The Ruddy Turnstone is one of my favorite migratory shorebirds. The combination of spunky attitude and gorgeous plumage make it hard to overlook.

The males in breeding plumage are spectacular!

Equally at home on sandy beaches and rocky shores, this bird has a unique eating style.

“An opportunistic feeder, the Ruddy Turnstone feeds on rocky and sandy beaches during winter and on migration, by turning over rocks, pebbles, seaweeds, shells, and other items with its stout, strong, and slightly upturned upper mandible, also used to probe, jab, and dig for food in winter and summer. Its diet when breeding is predominantly dipteran insects (flies). Outside the breeding season, foods are extremely diverse, ranging from coastal invertebrates to small fish, carrion, human garbage, and unattended eggs of other avian species.”

In this companion video, you can view the foraging habits of the Ruddy Turnstone.

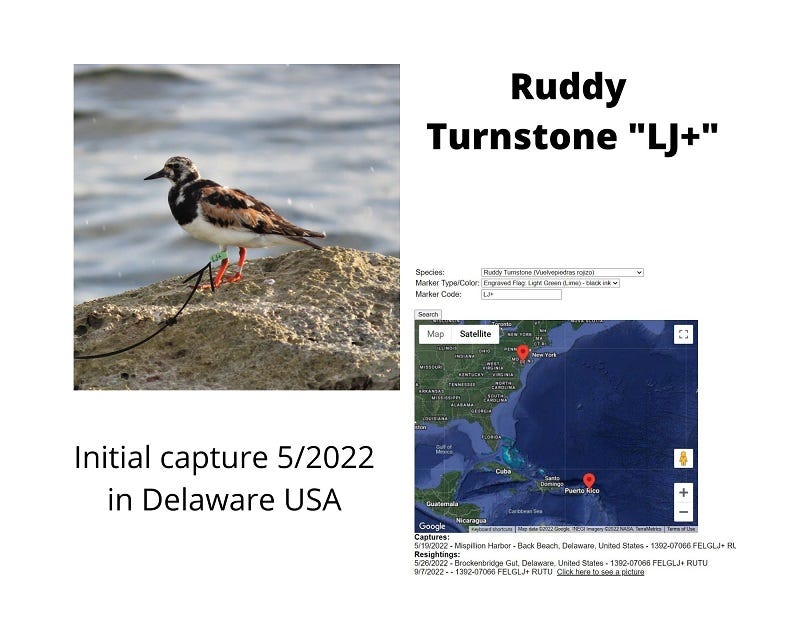

Beyond their looks, is a far more enticing feature of this species. They often arrive on our shores wearing “jewelry” in the form of bands and flags.

While I see several different banded species throughout the year, Ruddy Turnstones are seen with the most frequency and repetition. This is most likely due to their high rate of site fidelity.

“Site fidelity, the tendency to return to a previously visited site, is commonly observed in migratory birds. This behaviour would be advantageous if birds returning to the same site, benefit from their previous knowledge about local resources.”

They act much like Anguilla’s “Snowbirds” - a term given to tourists who spend each winter on Anguilla. They arrive in the Fall and head north in the Spring to warmer temperatures avoiding the worst winter weather.

The trick to identifying these birds is to spot them among the crowd often at great distances. For example:

Finding this guy.

In this group of Ruddies on the beach.

Once I spot the bird it is important to get a clear shot of the flag to reveal the code. It’s sort of like a treasure hunt.

The resighting information is entered into my bandedbirds.org account. Once accepted, a full accounting of the original banding date and location are provided along with any resighting records.

The beauty of the band/flag combination is there is no need to recapture the bird. Anyone who sees the bird along its flight path can report the resighting information.

While a few birds are banded in South America, most come from the eastern seaboard states like New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland - all located along the Atlantic Flyway.

I find it hard not to get attached to frequent visitors like the Jersey Bird “EAE.” This individual has visited West End Pond regularly since 2015. The original capture and banding was in May 2014 on Kimbles Beach in New Jersey.

The guy who truly stole my heart was my first banded Ruddy Turnstone - “2EY.” I initially encountered this gentleman on the beach in Sandy Ground in 2012. It was happily dodging the waves with its flock. Also a Jersey Bird it was banded at Reeds Beach in New Jersey in 2011.

This bird spent its days wandering the beaches by Elvis or behind the Pump House on Road Salt Pond from August to February each year. I could set my watch to his arrival and he never disappointed.

After an absence in 2017, I was excited to see him in 2018. His arrival meant he survived Hurricane Irma, unlike many others. Instinct must have cautioned this bird to avoid Anguilla and seek safer territory during one of the island’s worst storms.

While the longest-known surviving Ruddy Turnstone was 19, their average life expectancy in the wild is 6 to 7 years.

In October 2020 I observed “2EY” foraging in his favorite spot on the pond. However, his right foot was missing. It did not stop him from feeding happily with his flock. However, a bird with one foot is at a severe disadvantage and the odds of long-term survival are small.

As I drove away I was acutely aware that this would be our last encounter. At 9 years of age, he had beat the odds. It did not make the sadness in my heart any easier.

On the bright side, “2EY” was a true “Snowbird” lucky to spend his winters on Anguilla’s beautiful shores and wetlands. Every time I visit his special spot, I think of all the amazing moments we shared.

There is no question that the data provided from bird banding is important to the survival of many migratory species. Protecting both breeding and overwintering habitats is essential to that survival. Perhaps one day my resighting reports will give ammunition to more environmentally conscious politicians to preserve Anguilla’s critical migratory bird habitats.

Excellent, as always, Thank you Jackie!

Fascinating!! Thank you Jackie! This morning while enjoying an early coffee on my porch i was marveling at semipalmated plovers and sandpipers (least or semis) enjoying breakfast as the tide crept in. Was wondering if we’d see them in Anguilla in March. Thank you for educating us and sharing so much information. Now we will look for the tag team!! 🙏🏽😘